26 July 2020

Dearest Fazal,

Today is my father’s birthday. He is eighty-seven years old. He told he me doesn’t want to live. His legs can barely hold his weight without buckling beneath him. My father is a proud man. But then, I see how engaged he is in the world, from politics to wanting to know each detail of each member in our family and I think he will live through this pandemic. He was married seven months ago and is in love with a woman named Jan. He reads a book a day. He can quote the batting averages of every baseball player in the national league and as a life-long republican he loathes what this president is doing to America. And then I recall his 40th> birthday, when he said to all of us on that occasion that he had nothing to live for—My mother wrapped each of his presents in black.

What Does It Mean To Be A Man?

I

“By God, no brother of mine is going to die on the factory floor,” he said to the men around him. “Goddammit, help me.”

II

“He’s not a dog,” the man said to his wife as they were driving home late at night.

“He’s a little boy in a brown dog suit.” The dog-boy turned to the woman and snarled a grin.

III

“Forgive me,” he wrote to his daughter and then lit another cigarette. There, he had said it, no need to mail the letter.

IV

“Gentlemen, I appreciate the fact that my sons brought you to the house to talk to me about moving to the retirement home. Your presentation was impressive, but I’m not going anywhere.” He snapped a match off his fingernail. A week later he died in his own bed and was buried with his ham radio set.

V

“I said I don’t want to talk about it—”

Women, most women, always want to talk about it. “It” being anything on their minds from the intricacies of family life to the whispers after love-making or, upon going to any party, asking if she is too fat or to too skinny or just right or, afterwards, if she said too much or not enough or why he just won’t tell her what he is thinking.

Women want to talk.

I often wonder what men want.

Of course, I realize you can’t generalize or stereotype gender or take anything for granted from anyone. But I do wonder. And it is a relief that the “what it means to be a man” is so much more open as is the notion of “what it means to be a woman,” or if one identifies as queer, than how customs and mores were ascribed to our parents and grandparents and previous generations.

The beauty of gender fluidity in the 21st> century and the freedom that LGBTQ communities have brought into a global collective consciousness is freeing. To be queer is to be oneself and not stuck in any binary of he or she, him or her but rather they, them, and theirs. Pronouns are receptors to identity, a matter of respect, not simply modifiers of nouns—a person, place, or thing—but part of an evolving language, a broadening and deepening of the discourse between human beings.

What a relief.

I remember when I first met Louis Gakumba, who would become our son, in Rwanda. He would walk with his friends and hold hands. This was the custom. To my eye, it was such a lovely expression between men. There was nothing self-conscious about it.

And when he came to America, one of the first places we went together as a family was to Yellowstone. I remember walking behind Brooke and Louis in the Norris Geyser Basin with steam rising all around us and an occasional geyser erupting. Though my delight was in sharing the thermal activity before us, it was heightened in watching these two men I loved holding hands as they walked the wooden boardwalk between the wonders of America’s first national park in Montana. It all felt so tender.

Louis no longer holds Brooke’s hand. He has assimilated himself into the norms of this country. Nor does he hold any man’s hand in America because it signals something else, especially among the men in our family, firmly grounded in the mythos of the American West. Guns, boots, and brawn. This saddens me.

Linda Asher, my surrogate mother, sister, and friend is eighty-seven (the same age as my father). We hold each others’ hands when we walk the streets of New York, day or night in any season. It offers us both solace and pleasure. I have watched older women do this in Italy, France, and Spain, and all over the world. It touches me as I watch other women touch each other.

I want to keep this tradition alive among my own friendships with women and men and members of my own family. Especially now, in this era of the coronavirus, where we can touch no one save our closest intimates who we have sheltered in place with together.

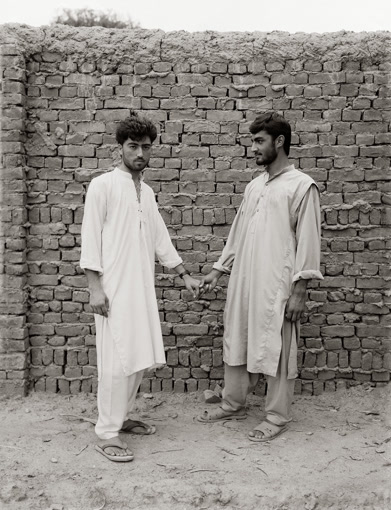

The two young Pakistani men dressed in white tunics standing in front of a brick wall are holding hands. They remind me that touching matters, holding hands matters, connecting without words, something akin to electricity moves lovingly between us.

Always,

Terry